( Add the English translation of the Van Gogh letter)

Van Gogh's paintings ~ accuse the contemporary church organization of corruption; the church collusion with powerful people, regardless of the weak, regardless of justice ... the words of the Bible at the time, such as extinguished candles as bleak.

梵谷的畫~控訴當代教會組織敗壞;教會與有權有勢的人勾結,不顧弱勢、不顧公義…聖經的話語在當時如熄滅的蠟燭般黯淡無光。

梵谷的人生第一志願是效法耶穌,傳道並行道,而非自少就想當藝術家。當年20幾歲的他因去礦區向貧困的礦工傳福音,因礦坑常常發生爆炸等災變造成極大傷亡,身為傳道人的他幫忙很悲慘的礦工向老闆談判爭取傷亡補助、改善職場環境以降低傷亡之類的…不料他竟被教會高層威脅不准替工人發聲…後還被教會組織高層解職了!

身為傳道的他為災變不斷受苦的礦工講話,竟被教會組織以他不適任為由開除,無人因他堅持真理仿效耶穌幫他在教會內講一句話,包括他隸屬於荷蘭歸正教派的牧師爸爸,據梵谷相關書籍提及那差派傳道至礦區的教會學校背後金主就是礦坑老闆,梵谷親筆書信輔佐見證此點…被解職後梵谷仍繼續去礦區跟窮人傳福音,直至因麵包問題不得不另作打算!之後他拒絕再出席教堂聚會,因此還被他爸趕出家門。

當年的他太年輕!誤以為那些教會組織的頭是耶穌基督因此受創很深!他是曾有些跌倒,他雖從此後終身幾乎未再出席教會活動,但看他書信我個人認定梵谷終生都是效法耶穌的基督徒,他是領受主耶穌的差遣,畫圖畫到就像麥子被磨碎為止…他書信有留下不少證言…我奉差遣找人同工傳揚梵谷傳道的遺願…及為他在華人世界翻案…花時間了解後開始看他留下的書信,感人震撼性不亞於他的畫作啊!且同樣創作量驚人規模龐大!荷蘭梵谷博物館聘請數十位專家耗費數十年才完成他全部信件的註釋工作,已全公開在官網。

可嘆世人大多只知他是藝術家,我深覺他根本是殉道的傳道人。以下是我整理列出的極小部分他書信翻譯,會繼續加油!

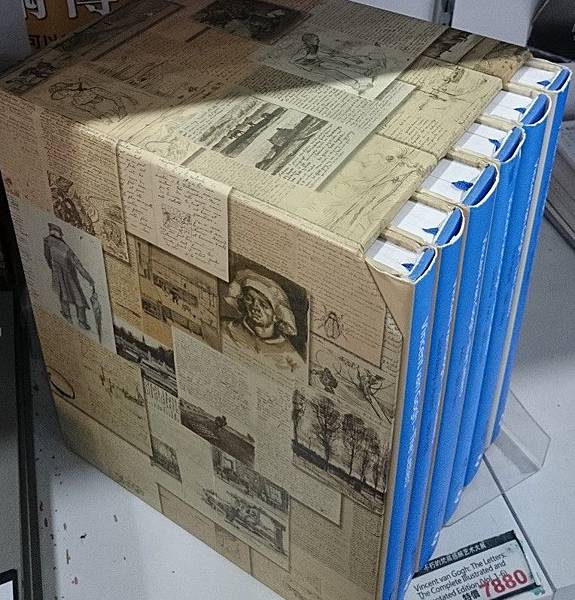

梵谷書信全集 此為英文版全集6巨冊 可見書信內容有多龐大 標價7880是人民幣 我在上海梵谷相關展覽首次看到的 網路可購買到此英文版 目前出的中文版都不是所謂全集

梵谷書信全集~封面 其中一冊的封面 取自他的親筆書信 書信集應含三種歐系語言

梵谷書信全集~親筆信 書信集其中一內頁 他書信常來個插畫輔佐他所寫的

梵谷書信全集英文版網路購買~http://thamesandhudsonusa.com/books/vincent-van-gogh-the-letters-the-complete-illustrated-and-annotated-edition-hardcover

梵古博物館的官網中有詳盡的書信內容:(以下為網址點進信件部份內容中譯整理)http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters.html

082

To Theo van Gogh. Ramsgate, Friday, 12 May 1876.

http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let082/letter.html

My dear Theo,

Thanks for your letter; I also like ‘Tell me the old, old story’1 very much. I first heard it sung in Paris, in the evening in a small church I used to attend sometimes. No. 122 is also beautiful. I regret not having gone to hear Moody and Sankey when they were in London. .3There’s such a yearning for Religion among the people in those big cities. Many a worker in a factory or shop has had a remarkable, pure, pious youth. But city life often takes away ‘the early dew of morning’,4 yet the yearning for ‘the old, old story’ remains, the bottom of one’s heart remains the bottom of one’s heart. In one of his books, Eliot describes the 1v:2 life of factory workers &c. who have joined a small community and hold religious services in a chapel in ‘Lantern Yard’, and he says it is ‘God’s Kingdom upon earth’,5nothing more nor less.

And there’s something moving about seeing the thousands now flocking to hear those evangelists … … …

Notes(the study of the Van Gogh Museum梵谷博物館的研究注釋)

3. Dwight Lyman Moody, an American evangelist, drew large crowds in the United States and led wide-ranging evangelization campaigns in both the United States and England. The singer and song writer Ira David Sankey was his accompanist and travelling companion. Sankey’s hymns were published in two volumes, Sacred songs and solos (1873) and Gospel hymns (1875-1891), both of which enjoyed widespread popularity.

Van Gogh refers here to numerous evangelical gatherings, organized by Moody and Sankey, which were held in London between February and July 1875. An illustrated account of the service held in The Agricultural Hall at Islington appeared in The Graphic 11 (20 March 1875), pp. 270, 276-277. See also W.R. Moody, The life of Dwight L. Moody. London n.d.

… … …大城巿裡有些人如此渴求宗教。許多工廠或商店裡的僱工都有一個虔誠的童年。但是城市生活有時候拭去「朝露」。對「古老故事」的渴望仍然存在;在心靈深處的東西,永遠留在那兒。我非常喜歡:「告訴我古老的故事」---我第一次聽到這句話時,是在巴黎的一個晚上,在我常去的一間小教堂裡。艾略特(19世紀英國女小說家)在她的一本小說裡,描寫工廠工人的生活,他們組成一個社區,並在燈籠廠的附屬禮拜堂做禮拜。看到成千的工人羣聚來傾聽福音,真是動人的一幕。

084

To Theo van Gogh. Welwyn, Saturday, 17 June 1876.

http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let084/letter.html

My dear Theo,

Last Monday I left Ramsgate for London. That’s a long walk indeed,2 and when I left it was awfully hot and it remained so until the evening, when I arrived at Canterbury. That same evening I walked a bit further until I came to a couple of large beeches and elms next to a small pond, where I rested for a while. In the morning at half past 3 the birds began to sing upon seeing the morning twilight, and I continued on my way. It was good to walk then. In the afternoon I arrived at Chatham, where, in the distance, past partly flooded, low-lying meadows, with elms here and there, one sees the Thames full of ships. It’s always grey weather there, I think. … … …

上星期一,我從蘭茲吉特徒步到倫敦;那是一次長途的步行,從我出發直到黃昏抵達坎特勃里時,天氣一直都很熱。傍晚,我又走了一點路,到了小池邊的幾棵大山毛櫸和榆樹下,才休息一會兒。清晨三點半,鳥兒開始在曙光裡囀唱,我再度上路。這時候走起來很舒服。下午抵達占松,眼前展現一片榆樹間生、半浸在水裡的低草,可遠眺船隻擁擠的泰晤士河;我相信那兒的氣候常年陰霾。… … …

I stayed in London for two days and often ran from one end of the city to the other in order to see various people, including a minister to whom I’d written.3 Herewith a translation of the letter,4 I’m 1v:2 sending it to you because you should know that the feeling I have as I start out is ‘Father, I am not worthy!’5 and ‘Father be merciful to me!’6 Should I find anything it will probably be a situation somewhere between minister and missionary, in the suburbs of London among working folk. Don’t speak about this to anyone, Theo. My salary at Mr Stokes’s will be very small. Probably only board and lodging and some free time in which to teach, or if there’s no free time, at most 20 pounds a year.

…. In the afternoon at 5, I was with our sister and was very glad to see her. She looks well and you would be as pleased with her room as I am, with ‘Good Friday’, ‘Christ in the Garden of Olives’, ‘Mater Dolorosa’9 &c. with ivy around them instead of frames……

Your loving brother

Vincent

我在倫敦逗留了兩天,從一區奔波到另一區去會見不同的人,我寫了一封信給一位牧師:… … …

Rev. Sir.

A clergyman’s son, who, because he must work to earn a living, has no money and no time to study at King’s College,10 and who, besides that, is already a couple of years older than is usual for someone starting there, and has not even begun on the preparatory studies of Latin and Greek, would, in spite of everything, dearly like to find a situation connected with the church, even though the position of a clergyman who has had college training is beyond his reach.

My father is a clergyman in a village in Holland. When I was 11 years old I started going to school and stayed there until I was 16.11 At that time I had to choose a profession and didn’t know what to choose. Through the offices of one of my uncles,12 an associate in the firm of Goupil & Co., art dealers and publishers of engravings, I was given a position in his branch at The Hague. I worked for the firm for 3 years. From there I went to London to learn English, and after 2 years from there to Paris. Forced by various circumstances to quit the firm, however, I left Messrs G.&Co. and have since taught for 2 months at Mr Stokes’s school at Ramsgate. As my goal is a situation connected with the church, however, I must look further. 1r:4

Although I have not been trained for the church, perhaps my past life of travelling, living in various countries, associating with a variety of people, rich and poor, religious and not religious, working at a variety of jobs, days of manual labour in between days of office work &c., perhaps also my speaking various languages, will compensate in part for my lack of formal training. But what I should prefer to give as my reason for commending myself to you is my innate love of the church and that which concerns the church, which has at times lain dormant, though it awakened repeatedly, and – if I may say so, despite feelings of great inadequacy and shortcoming – the Love of God and of humankind. And also, when I think of my past life and of my father’s house in that Dutch village, a feeling of ‘Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son,13 make me as one of thy hired servants.14 Be merciful to me.’15 When I was living in London I often attended your church and I have not forgotten you. Now I am asking you for a recommendation in my search for a situation, and to keep a fatherly eye on me should I find such a situation. I have been left very much to myself; I believe that your fatherly eye could do me good, now that

The early dew of morning

has passed away at noon.16

Thanking you in advance for whatever you may be willing to do for me...

主席先生:

一位牧師的兒子,必須工作維生,沒有時間或金錢進入金恩學院研習,![]() 況且比一般入學年齡長了幾歲,儘管如此,將樂於尋覓一與教會相關的職位。

況且比一般入學年齡長了幾歲,儘管如此,將樂於尋覓一與教會相關的職位。

我父親是荷蘭一鄉村的牧師。我十一歲上學,十六歲離鄉。然後我必須選擇一項職業,但不知擇取什麼才好。透過我一位伯父,谷披爾公司---美術商和版畫出版商---的合夥人之介紹,我在他海牙的公司裡謀得一職,工作了三年。後來到倫敦學習英文,兩年後離開倫敦前往巴黎。

由於環境變異所迫,我離開谷披爾,在蘭茲吉特的史托克先生所辦的學校裡,教了兩個月的書。但是因爲我的目標是在一項與教會有關的職業上,我應該另外找工作;雖然我並未受過爲教會工作而設的教育,但我的旅行,以及我在多個國家與貧或富、教徒或不信教等不同人民混居的經驗,加上從事勞力或坐辦公桌等各色工作的歷驗,或許可以補償我未曾進大學的缺陷。---而我寧可以此理由向你做自我推薦:我天生熱愛教會和一切與之有關的事,這份感情偶而會沈入睡眠狀態,但每次都再度被喚醒;同時也由於我「對上帝和人類的愛」---縱使帶著極大的不當和不足的感覺,但願我可以説岀這句話。… … …

085

To Theo van Gogh. Isleworth, Monday, 3 or Tuesday, 4 July 1876.

http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let085/letter.html

… … … Being a London missionary is rather special, I believe; one has to go around among the workers and the poor spreading God’s word and, if one has some experience, speak to them, track down and seek to help foreigners looking for work, or other people who are in some sort of difficulty, etc. etc. Last week I was in London a couple of times to find out if there’s a possibility of my becoming one.5 Because I speak various languages and have tended to associate, especially in Paris and London, with people from the poorer classes and foreigners, and being a foreigner myself, I may well be suited 1v:3 to this, and could become so more and more.

To do this, however, one has to be at least 24 years old, and so in any case I still have a year to wait … … …

… … … 我想當個倫敦的傳教師,該是一項特殊的職業;他必得穿梭於工人和窮人之間以宣講聖經,如果他有經驗的話,可以跟他們聊天,看出正在尋找工作的異鄉人或其他陷於困境的人,並設法幫助他們。由於我會說好幾種語言,尤其是在巴黎和倫敦時曾與下階層和外邦人混居,我本身又是一個外邦人,因此可能很適合從事這項工作,而這個可能性愈來愈大;所以我去過那兒二、三次,想看看有沒有機會。然而,至少要到了二十四歲才能成爲倫敦傳教師:總之,我必須再等一年。… … …

155

To Theo van Gogh. Cuesmes, between about Tuesday, 22 and Thursday, 24 June 1880.

http://vangoghletters.org/vg/letters/let155/letter.html

My dear Theo,

It’s with some reluctance that I write to you, not having done so for so long,1 and that for many a reason. Up to a certain point you’ve become a stranger to me, and I too am one to you, perhaps more than you think; perhaps it would be better for us not to go on this way.

It’s possible that I wouldn’t even have written to you now if it weren’t that I’m under the obligation, the necessity, of writing to you. If, I say, you yourself hadn’t imposed that necessity. I learned at Etten2 that you had sent fifty francs for me; well, I accepted them.3 Certainly reluctantly, certainly with a rather melancholy feeling, but I’m in some sort of impasse or mess; what else can one do? … … …

You must know that it’s the same with evangelists as with artists. There’s an old, often detestable, tyrannical academic school, the abomination of desolation,10 in fact — men having, so to speak, a suit of armour, a steel breastplate of prejudices and conventions. Those men, when they’re in charge of things, have positions at their disposal, and by a system of circumlocution11 seek to support their protégés, and to exclude the natural man from among them.

Their God is like the God of Shakespeare’s drunkard, Falstaff, ‘the inside of a church’;12 d in truth, certain evangelical (???) gentlemen find themselves, by a strange conjunction (perhaps they themselves, if they were capable of human feeling, would be somewhat surprised) find themselves holding the very same point of view as the drunkard in spiritual matters. But there’s little fear that their blindness will ever turn into clear-sightedness on the subject.13

This state of affairs has its bad side for someone who doesn’t agree with all that, and who protests against it with all his heart and with all his soul and with all the indignation of which he is capable.

Myself, I respect academicians who are not like those academicians, but the respectable ones are more thinly scattered than one would believe at first glance. Now one of the reasons why I’m now without a position, why I’ve been without a position for years, it’s quite simply because I have different ideas from these gentlemen who give positions to individuals who think like them.

It’s not a simple matter of appearance, as people have hypocritically held it against me, it’s something more serious than that, I assure you.

Why am I telling you all this? — not to grumble, not to apologize for things in which I may be more or less wrong, but quite simply to tell you this: on your last visit, last summer,14 when we walked together near the disused mine they call La Sorcière,15 you reminded me that there was a time when we also walked together near the old canal and mill of Rijswijk,16 and then, you said, we were in agreement on many things, but, you added — you’ve really changed since then, you’re not the same any more. Well, that’s not quite how it is; what has changed is that my life was less difficult then and my future less dark, but as far as my inner self, as far as my way of seeing and thinking are concerned, they haven’t changed. But if in fact there were a change, it’s that now I think and I believe and I love more seriously what then, too, I already thought, I believed and I loved.

So it would be a misunderstanding if you were to persist in believing that, for example, I would be less warm now towards Rembrandt or Millet or Delacroix, or whomever or whatever, because it’s the opposite. But you see, there are several things that are to be believed and to be loved; there’s something of Rembrandt in 1r:4 Shakespeare17 and something of Correggio or Sarto in Michelet, and something of Delacroix in V. Hugo, and in Beecher Stowe there’s something of Ary Scheffer. And in Bunyan there’s something of M. Maris or of Millet, a reality more real than reality, so to speak, but you have to know how to read him; then there are extraordinary things in him, and he knows how to say inexpressible things; and then there’s something of Rembrandt in the Gospels or of the Gospels in Rembrandt, as you wish, it comes to more or less the same, provided that one understands it rightly, without trying to twist it in the wrong direction, and if one bears in mind the equivalents of the comparisons, which make no claim to diminish the merits of the original figures.

If now you can forgive a man for going more deeply into paintings, admit also that the love of books is as holy as that of Rembrandt, and I even think that the two complement each other.

I really love the portrait of a man by Fabritius, which one day, also while taking a walk together, we looked at for a long time in the Haarlem museum.18 Good, but I love Dickens’s ‘Richard Cartone’ in his Paris et Londres en 1793 just as much,19 and I could show you other strangely vivid figures in yet other books, with more or less striking resemblance. And I think that Kent, a man in Shakespeare’s King Lear, is just as noble and distinguished a character as any figure of Th. de Keyser, although Kent and King Lear20 are supposed to have lived a long time earlier. To put it no higher, my God, how beautiful that is. Shakespeare — who is as mysterious as he? — his language and his way of doing things are surely the equal of any brush trembling with fever and emotion. But one has to learn to read, as one has to learn to see and learn to live.21

So you mustn’t think that I’m rejecting this or that; in my unbelief I’m a believer, in a way, and though having changed I am the same, and my torment is none other than this, what could I be good for, couldn’t I serve and be useful in some way, how could I come to know more thoroughly, and go more deeply into this subject or that? Do you see, it continually torments me, and then you feel a prisoner in penury, excluded from participating in this work or that, and such and such necessary things are beyond your reach. Because of that, you’re not without melancholy, and you feel emptiness where there could be friendship and high and serious affections, and you feel a terrible discouragement gnawing at your psychic energy itself, and fate seems able to put a barrier against the instincts for affection, or a tide of revulsion that overcomes you. And then you say, How long, O Lord!22 Well, then, what can I say; does what goes on inside show on the outside? Someone has a great fire in his soul and nobody ever comes to warm themselves at it, and passers-by see nothing but a little smoke at the top of the chimney and then go on their way. So now what are we to do, keep this fire alive inside, have salt in ourselves,23 wait patiently, but with how much impatience, await the hour, I say, when whoever wants to, will come and sit down there, will stay there, for all I know? May whoever believes in God await the hour, which will come sooner or later.

Now for the moment all my affairs are going badly, so it would seem, and that has been so for a not so inconsiderable period of time, and it may stay that way for a future of longer or shorter duration, but it may be that after everything has seemed to go wrong, it may then all go better. I’m not counting on it, perhaps it won’t happen, but supposing there were to come some change for the better, I would count that as so much gained; I’d be pleased about it, I’d say, well then, there you are, there was something, after all. 2r:5

But you’ll say, though, you’re an execrable creature since you have impossible ideas on religion and childish scruples of conscience. If I have any that are impossible or childish, may I be freed from them; I’d like nothing better. But here’s where I am on this subject, more or less. You’ll find in Souvestre’s Le philosophe sous les toits how a man of the people, a simple workman, very wretched, if you will, imagined his mother country,24 ‘Perhaps you have never thought about what your mother country is, he continued, putting a hand on my shoulder; it’s everything that surrounds you, everything that raised and nourished you, everything you have loved. This countryside that you see, these houses, these trees, these young girls, laughing as they pass by over there, that’s your mother country! The laws that protect you, the bread that is the reward of your labour, the words that you exchange, the joy and sadness that come to you from the men and the things among which you live, that’s your mother country! The little room where you once used to see your mother, the memories she left you, the earth in which she rests, that’s your mother country! You see it, you breathe it everywhere! Just think, your rights and your duties, your attachments and your needs, your memories and your gratitude, put all that together under a single name, and that name will be your mother country.’

Now likewise, everything in men and in their works that is truly good, and beautiful with an inner moral, spiritual and sublime beauty, I think that that comes from God, and that everything that is bad and wicked in the works of men and in men, that’s not from God, and God doesn’t find it good, either. But without intending it, I’m always inclined to believe that the best way of knowing God is to love a great deal.25 Love that friend, that person, that thing, whatever you like, you’ll be on the right path to knowing more thoroughly, afterwards; that’s what I say to myself. But you must love with a high, serious intimate sympathy, with a will, with intelligence, and you must always seek to know more thoroughly, better, and more. That leads to God, that leads to unshakeable faith.

Someone, to give an example, will love Rembrandt, but seriously, that man will know there is a God, he’ll believe firmly in Him.

Someone will make a deep study of the history of the French Revolution — he will not be an unbeliever, he will see that in great things, too, there is a sovereign power that manifests itself.

Someone will have attended, for a time only, the free course at the great university of poverty, and will have paid attention to the things he sees with his eyes and hears with his ears,26 and will have thought about it; he too, will come to believe, and will perhaps learn more about it than he could say.

Try to understand the last word of what the great artists, the serious masters, say in their masterpieces; there will be God in it. Someone has written or said it in a book, someone in a painting.

And quite simply read the Bible, and the Gospels, because that will give you something to think about, and a great deal to think about and everything to think about, well then, think about this great deal, think about this everything, it raises your thinking above the ordinary level, despite yourself. Since we know how to read, let’s read, then!

Now, afterwards, we may well at times be a little absent-minded,27 a little dreamy; there are those who become a little too absent-minded, a little too dreamy; that happens to me, perhaps, but it’s my own fault. And after all, who knows, wasn’t there some cause; it was for this or that reason that I was absorbed, preoccupied, anxious, but you get over that. The dreamer sometimes falls into a pit, but they say that afterwards he comes up out of it again. 2v:6

And the absent-minded man, at times he too has his presence of mind, as if in compensation. He’s sometimes a character who has his raison d’être for one reason or another which one doesn’t always see right away, or which one forgets through being absent-minded, mostly unintentionally. One who has been rolling along for ages as if tossed on a stormy sea arrives at his destination at last; one who has seemed good for nothing and incapable of filling any position, any role, finds one in the end, and, active and capable of action, shows himself entirely different from what he had seemed at first sight.

I’m writing you somewhat at random whatever comes into my pen; I would be very happy if you could somehow see in me something other than some sort of idler.

Because there are idlers and idlers, who form a contrast.

There’s the one who’s an idler through laziness and weakness of character, through the baseness of his nature; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one.28 Then there’s the other idler, the idler truly despite himself, who is gnawed inwardly by a great desire for action, who does nothing because he finds it impossible to do anything since he’s imprisoned in something, so to speak, because he doesn’t have what he would need to be productive, because the inevitability of circumstances is reducing him to this point. Such a person doesn’t always know himself what he could do, but he feels by instinct, I’m good for something, even so! I feel I have a raison d’être! I know that I could be a quite different man! For what then could I be of use, for what could I serve! There’s something within me, so what is it! That’s an entirely different idler; you may, if you think fit, take me for such a one.

In the springtime a bird in a cage29 knows very well that there’s something he’d be good for; he feels very clearly that there’s something to be done but he can’t do it; what it is he can’t clearly remember, and he has vague ideas and says to himself, ‘the others are building their nests and making their little ones and raising the brood’, and he bangs his head against the bars of his cage. And then the cage stays there and the bird is mad with suffering. ‘Look, there’s an idler’, says another passing bird — that fellow’s a sort of man of leisure. And yet the prisoner lives and doesn’t die; nothing of what’s going on within shows outside, he’s in good health, he’s rather cheerful in the sunshine. But then comes the season of migration. A bout of melancholy — but, say the children who look after him, he’s got everything that he needs in his cage, after all — but he looks at the sky outside, heavy with storm clouds, and within himself feels a rebellion against fate. I’m in a cage, I’m in a cage, and so I lack for nothing, you fools! Me, I have everything I need!30 Ah, for pity’s sake, freedom, to be a bird like other birds! 2v:7

An idle man like that resembles an idle bird like that.

And it’s often impossible for men to do anything, prisoners in I don’t know what kind of horrible, horrible, very horrible cage. There is also, I know, release, belated release. A reputation ruined rightly or wrongly, poverty, inevitability of circumstances, misfortune; that creates prisoners.

You may not always be able to say what it is that confines, that immures, that seems to bury, and yet you feel I know not what bars, I know not what gates — walls.

Is all that imaginary, a fantasy? I don’t think so; and then you ask yourself, Dear God, is this for long, is this for ever, is this for eternity?

You know, what makes the prison disappear is every deep, serious attachment. To be friends, to be brothers, to love; that opens the prison through sovereign power, through a most powerful spell. But he who doesn’t have that remains in death. But where sympathy springs up again, life springs up again.

And the prison is sometimes called Prejudice, misunderstanding, fatal ignorance of this or that, mistrust, false shame.

But to speak of something else, if I’ve come down in the world, you, on the other hand, have gone up. And while I may have lost friendships, you have won them. That’s what I’m happy about, I say it in truth, and that will always make me glad. If you were not very serious and not very profound, I might fear that it won’t last, but since I think you are very serious and very profound, I’m inclined to believe that it will last. 2r:8

But if it became possible for you to see in me something other than an idler of the bad kind, I would be very pleased about that.

And if I could ever do something for you, be useful to you in some way, know that I am at your service. Since I’ve accepted what you gave me, you could equally ask me for something if I could be of service to you in some way or another; it would make me happy and I would consider it a sign of trust. We’re quite distant from one another, and in certain respects we may have different ways of seeing, but nevertheless, sometime or some day one of us might be able to be of use to the other. For today, I shake your hand, thanking you again for the kindness you’ve shown me.

Now if you’d like to write to me one of these days, my address is care of C. Decrucq, rue du Pavillon 8, Cuesmes, near Mons,31 and know that by writing you’ll do me good.

Yours truly,

Vincent

… … … 我必須告訴你,傳道者的情形和藝術家的一樣。那是一所古老的學院,專橫可憎,累積著恐懼,裡頭的人穿戴偏見與陋習的胸甲;那些人一居高位掌大權,便惡性循環地袒護黨羽,排斥別人。他們的上帝就像醉酒的浮士德(Falstaff莎士比亞筆下一個愛吹牛的角色)心目中的上帝,是「教會裡的東西」!的確有些傳播福音的紳士們在一個奇異的機會裡,發現自己對於精神事物的觀點,跟那醉漢的相同 (假若他們賦有人類情感的話,發現此點,或許要感到驚奇了)。

我本人尊敬學者,但是值得尊敬的人數比一般人所相信的更稀少。我之所以失業,失業了好幾年的原因之一,純粹是由於我抱持的觀念,跟把職位賜給合乎己意者的那批紳士相異。那不單是關乎服飾的問題;我敢斷定那是一個嚴肅得多的問題。

你說:「你對於宗教有不可能的看法,對於良心有幼稚的顧忌。我認爲一切真正美好的,屬於內潛精神的事物,以及人類和其作品裡的昇華之美,無不來自上帝;而人類和其作品裡的一切惡質與錯誤,都不是屬於上帝的,上帝也不贊同它們。我常想認識上帝的最佳途徑,是去喜愛很多事物,去愛一位朋友、一個妻子、一件事情,任何你喜歡的東西,可是必須把崇高莊嚴的深密同情心、力量,以及智慧灌注到這個愛裡頭去,而且應該經常瞭解得更深丶更好丶更多。這是導向上帝,導向堅定信仰的路。

去年夏天你來看我的期間,我們在被人稱爲「女巫」的採掘場附近散步時,你提醒我有一次我們步行到里斯維克路的舊河道與磨坊一帶之情景。你説:「那時候,我們對許多事持有相同的看法。」可是你又説:「從那以後,你改變太多了,你己經不一樣了。」哎!這並不完全對哪!改變的是,那時候我的生命比較順利,我的前途似乎不這麼黑暗;至於内在的情狀、觀看事物的態度、思想方式,並沒有改變。如果説有什麼變化的話,則是:如今我更認真地去思考、信任、喜愛從前所思所信所愛的東西。

你若不斷地以爲我目前對於林布蘭特、米勒、德拉克洛瓦等人己經較不熱心了,那麼你就錯了,因爲事實正好相反。而你也明瞭一個人必須信任必須喜愛許多東西。林布蘭特的某些質素存在於莎士比亞裡、訶瑞喬的在於米齊列裡,德拉克洛瓦的在於雨果裡、林布蘭特的也在於福音書裡,或者你高興的話,也可以説福音書裡有林布蘭特的某些質素,班揚裡有米勒,史陀裡有謝費爾。

但願你能寬容一個人徹底的研究一幅畫,並且承認愛書正如林布蘭特一樣地衶聖,而我認爲兩者甚至是相輔相成的。我非常喜歡發伯利修所繪的一張肖像畫,有一天我們去參觀哈嵐的博物館時,曾經在它面前佇立良久。不錯,但我也喜歡狄更斯所撰「雙城記」裡的人物卡冬。老天,莎士![]() 比亞多美啊! 誰像他那麼神秘呢?他的語言與文體的確可以比美藝術家的畫筆。一個人必須學習怎麼讀,正如他必須學習怎麼活一樣。

比亞多美啊! 誰像他那麼神秘呢?他的語言與文體的確可以比美藝術家的畫筆。一個人必須學習怎麼讀,正如他必須學習怎麼活一樣。

因此,你不應該以爲我否定事物;在我的不忠實裡,我是頗爲忠實的;雖然改變了,我依然一樣,我唯一焦慮的是:我如何才能在這世上有用處?我不能一面服侍某一宗旨,而且同時對人有點好處嗎?我如何才能學![]() 習得更多?你瞧,這些事情繼續佔據我心,我又覺得被貧窮所禁錮,無法參與某些工作,某些必要的事物乃非我所能觸及。那是無時不憂鬱的一個因素,因而在可能有友情和熱烈愛情的地方,也會感到空虛;覺得一種可怕的沮喪噬蝕真正的精神力量;命運似乎在愛的本能上加設一道障籬,漲起一股厭惡的洪流叫人窒息。我不禁吶喊:「要多久呀,老天!亅

習得更多?你瞧,這些事情繼續佔據我心,我又覺得被貧窮所禁錮,無法參與某些工作,某些必要的事物乃非我所能觸及。那是無時不憂鬱的一個因素,因而在可能有友情和熱烈愛情的地方,也會感到空虛;覺得一種可怕的沮喪噬蝕真正的精神力量;命運似乎在愛的本能上加設一道障籬,漲起一股厭惡的洪流叫人窒息。我不禁吶喊:「要多久呀,老天!亅![]()

![]()

哎,我能說什麼呢?我們的内在思想,曾經顯露在外嗎?我們的靈魂裡,可能有一道大火,卻没有人來到這火前取暖;路過的人只看到一絲煙從煙囱裡出來,然後又向前走。此時,你說該做什麼呢?應該守望那道内在的火,在自我裡加點刺激,耐心地等待,但要有多少耐心去等待某人走來坐在火旁逗留的時辰降臨呢?

目前,我好像過得很不如意,這種情況已經持續了不算短的一段時間,往後可能還要繼續好些日子;可是,一切似乎都不對勁之後,大概就是一切都將順利起來的時候了。我並不倚賴它,它也許永不會發生,但是事態終將好轉的,屆時我該說:好不容易!你瞧,畢竟有些苗頭了!

如果你能在我身上看出一點閒散以外的質素,我會很快慰的。因爲閒散可分爲兩種類型,形成一個很大的比照。有些人的閒散來自怠惰與欠缺個性,來自本性的卑鄙。如果你高興,你可以把我歸入這一類。另一種人的![]() 閒散,是不顧自我的閒散,他的心神由於熱切渴求行動而消耗殆盡,因爲他似乎被囚禁在某種樊籠内。那是一種合理的或不合理的聲名墮落、貧窮、毁滅性的情況丶困逆的環境使人成爲囚犯的東西。此一牢獄也被稱爲偏見、誤解、對某一件事物致命地無知、不信任、佯裝的羞恥心。一個人往往說不清是什麼東西關閉了我們、限制了我們、埋葬了我們,然而卻感覺得出來某種籬笆、某種牆垣的存在。這麼樣的一個人往往不曉得他能做什麼,卻本能地有這個感覺:是的,我對某些事很在行;我的生命畢竟有個目標;我知道我可能是個與衆不同的人!我裡頭有些東西;那會是什麼呢?

閒散,是不顧自我的閒散,他的心神由於熱切渴求行動而消耗殆盡,因爲他似乎被囚禁在某種樊籠内。那是一種合理的或不合理的聲名墮落、貧窮、毁滅性的情況丶困逆的環境使人成爲囚犯的東西。此一牢獄也被稱爲偏見、誤解、對某一件事物致命地無知、不信任、佯裝的羞恥心。一個人往往說不清是什麼東西關閉了我們、限制了我們、埋葬了我們,然而卻感覺得出來某種籬笆、某種牆垣的存在。這麼樣的一個人往往不曉得他能做什麼,卻本能地有這個感覺:是的,我對某些事很在行;我的生命畢竟有個目標;我知道我可能是個與衆不同的人!我裡頭有些東西;那會是什麼呢?

你知道什麼把一個人從此一樊籠裏釋放出來嗎?那就是每一種莊嚴深刻的情感。朋友丶兄弟、愛人,他們以至高無上的神奇力量開啟了這個牢獄。同情心再生的地方,生命隨之復甦。

我必須循著我此刻所採取的路徑前進;若我不做任何事,不研讀、不再繼續追尋的話,我便迷失了。那我會真傷心的。那是我的態度;繼續走下去,這是必然的。但你會問:什麼是你的明確目標?那個目標將變得更明確,將慢慢地踏實地顯現出來,好比一張粗略的草圖變成一張素描,一張素描變成一幅畫,一點一滴地認真運作,仔細掌握那概念那稍縱即逝的思緒,直到它固定下來爲止。… … …

*以上整理自荷蘭梵谷博物館官網與《梵谷書簡全集》。

留言列表

留言列表